| Novelist Stephen King |

― Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

Another Mr. King quote! King's novels are fine, but I sure do love his quotes! I find them inspiring and with a few tweaks can be very applicable to the musical muse. Allow me to replace a few words...

“If you want to be a composer/musician/improviser, you must do two things above all others: listen a lot and compose/play/improvise a lot. There's no way around these two things that I'm aware of, no shortcut.”

- My variant of Stephen King's quote

That's basically it. I could end this post here. Mr. King has laid out a simple formula for mastery that cannot be denied. Listen and create. Repeat.

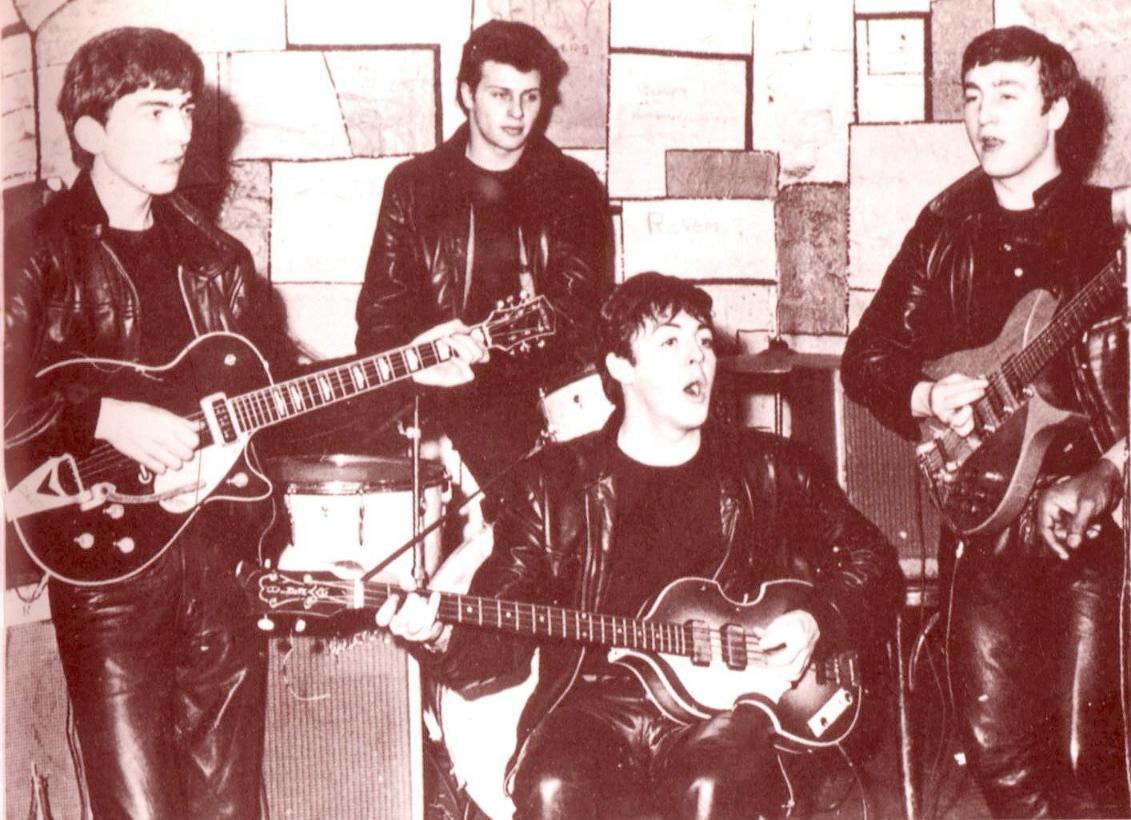

Malcolm Gladwell popularized the "10,000 hour" rule in his 2008 book Outliers. The summation of this rule is that it takes 10,000 hours of doing something to develop mastery. Gladwell cites cases from the Beatles cutting their teeth by playing cover songs in Hamburg dives to Bill Gates who had access to a computer in 1968 when they weren't as common as they were today.

An important aspect of this 10,000 hours is the idea of mastering what has already been created in your art form. The Beatles spent their time in Hamburg not writing original "creative" works. They covered American rock and roll songs. The U.S. troops station there demanded the music of Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, and Chuck Berry. This forced the Fab Four to develop a solid vocabulary of rock and roll. It taught them to groove. It taught them stage presence. It taught them about the art of songcraft. By the time they penned their first number one hit in England ("Please Please Me") they have logged in 10,000 hours of mastering the art of performing and writing a hit song.

An important aspect of this 10,000 hours is the idea of mastering what has already been created in your art form. The Beatles spent their time in Hamburg not writing original "creative" works. They covered American rock and roll songs. The U.S. troops station there demanded the music of Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, and Chuck Berry. This forced the Fab Four to develop a solid vocabulary of rock and roll. It taught them to groove. It taught them stage presence. It taught them about the art of songcraft. By the time they penned their first number one hit in England ("Please Please Me") they have logged in 10,000 hours of mastering the art of performing and writing a hit song.

This "10,000 rule" is based on the research of psychologist Anders Ericsson. It has its critics who feel this rule has been misused as it has become quoted in many pop-psychology articles and blogs. Merely putting in time won't make one a master the critics argue. Even Ericsson has said, “You don’t get benefits from mechanical repetition, but by adjusting your execution over and over to get closer to your goal.”

Everyone can be creative. It seems to be a trite statement but its true. On some level, everyone has the ability to be inspired. Even the beginner musician can experience the thrill of exploration that even the greatest musical innovators experience. It would be very frustrating if you had to lock in 10,000 hours BEFORE you could create.

However, you must know that these early creative attempts will not be original. They won't be masterpieces. They will probably not even be good. At least not without developing a solid foundation of skills and knowledge. It is impossible to create a truly unique, quality piece of work until you have created a LOT of derivative works.

Students with a creative urge are often frustrated by this. They have a strong desire to create something groundbreaking but they haven't yet mastered the basics. Without a command of what has already been created in their field, that won't know how to be original. What rules should you break? What is the basic vocabulary of style? What elements of preexisting works can be borrowed and combined to create new, original works?

A solid creative foundation needs:

- A command of musical elements (rhythm, melody, harmony, form, timbre)

- A deep knowledge of style and genre (not all styles and genres, but at least the ones in your purview)

- The study of repertoire in that genre from the earliest days to the present

- An apprenticeship of two types. A formal student-teacher relationship AND the tutelage of the great artists in the field through recordings and live performances.

- A venue. The student needs an outlet to showcase the mastery of the above.

In addition, you need to have a desire to explore. "What if?" should be a regular part of this stage.

- "What if I harmonize this melody in fourths?"

- "What if I play this tune in 7?"

- "What if I add more dissonance? More consonance?"

- "What if I add more space?"

- "What if I ..."

With each new question you will be creating something new. Evaluate the new product. If it is good, go on from there asking a new "what if" question. If it doesn't work out, ask a different question.

So wherever you are at in laying your foundation, ask these questions. Focus and develop your inner grit. And start clocking in some of those 10,000 hours!

No comments:

Post a Comment